This is a draft version of a chapter from John Saye’s book, Longevity and Other Stories. If you are daring, why not subscribe to my newsletter (they come few and far between), and I’ll send you a PDF copy of the book?

I sat back on my little porch, a balcony really, and looked out at the ocean. Blue-green as far as the eye could see, almost crystal clear towards the shore, a beach as clean as you could get. There were scattered umbrellas here and there in patterns of fuchsia and aquamarine, and white. Few people still, but the war was long over and, though everyone remembered it, no one remembered it. Does that make sense? It is the kind of thing that’s only ever talked about anymore in movies and on the Internet if you go back far enough, and since the browsers are still updating about a version number every five months, it’s harder and harder to find plug-ins that can translate the old stuff anymore.

The sky is clear. Only a few planes are up in it anymore, but those that are can carry five thousand people at a time. There are some smaller air vans around, but most of us just program our cars and let them do the work these days. They’ll find the best route, and take us there without having to ever refuel and streets are all but useless, but no longer all destroyed. We still like to pave walking paths and I like the bike trail I use from here to the store and back every day. Just a regular bike, you know, like when I was a kid. I like it. Had to order the thing from the other side of the planet, but that didn’t matter. Everything seems to ship overnight all the time, and I’ve put away enough money to be comfortable, but I’m still on the lookout for something to do, that’s all. I want to just find something.

Mary and I were married last year. I know that sounds odd, doesn’t it? Married Mary? I refused to use the term in front of her. I figure when you’ve got a name that invites the jokes you’ve heard them all right?

I do like the pelicans, though. They hover over my condo all the time, and yes, I feed them. They’ll eat anything. I was feeding them the remains of fish that I’d already cleaned as they sat there on the pier. (there’s a pretty good pier down on the shore about two buildings down.) They are like big walking trash buckets. I could probably have tossed my whole bag of fishing gear and they would have eaten it. They’re dumb, but I like them.

One of them comes to see me all the time. I call him Pete. No particular reason. I just like him. I know that it’s Pete because he’s missing his left eye, and he’s a little slower than the other pelicans.

After the war, most of the cities were destroyed.

We had a lot of crap to clean up, not to mention all the walkers we had to get rid of. That was a mess and a half.

We did the job, though, but there weren’t as many of us after the war. We’re doing fine now, and yes, everyone still gets the shot when they are born, but it was just too hard to stay settled in some areas. Anywhere that was cold was just out, and we kept moving further and further south. Some went east and west, but no one went north. Most people ended up on the coast somewhere. We didn’t have any boats in the water to pollute it with, most stuff being delivered by air freighter, and all the cars had little atomic power cells in them. Safe. Yes, I know what you’re thinking. But things never need a battery. I had my hover bike outfitted with one the year before last, and the car came after that, though I can hardly call the thing a car since my first car was a practically rusted-out Camaro from the 1980s.

The car, if you could call it that, is more like a traveling living room. It’s made up of a large bubble top surrounded by four repulsor plates and a small two-foot wall all the way around. Inside is a carpeted room under that domed ceiling with a table that stands, bolted to the floor on a chrome pole. Surrounding the table are a series of chairs. Four can sit at the table, and there is a three-seat couch at the back. There are also little monitors all over the place. You can watch films or listen to music as you safely glide to your next destination. It seems to take about an hour to get anywhere in the United States. (Or what’s left of the United States, let’s call it North America. That’s just the way I think sometimes.) and if you’re going overseas, it seems to take between an hour and three hours to get anywhere in the world.

That’s nothing to what we’re doing in space, though.

There’s a reason there aren’t more bodies out on the beach today. It’s the fact that we’ve confirmed the existence of life outside our solar system. People are out celebrating.

I was out getting away from the video screens for a minute, but we’ve been sending probes out to distant stars and though most haven’t gotten where they are going, the one to Alpha Centauri did. We’ve been watching the reports for a while now about all the planets we’re discovering there. The first one was a big gas giant, then several smaller ones, then the mother-load. We haven’t even fully explored our planets yet, but we’ve got this. The rocket landed on the fourth planet there and touched down after sensing a lot of heat that was moving around, and when the cameras turned on, there was this enormous great white bear-like thing, kind of like a polar bear but the size of a mastodon licking the camera. Once they figured out they couldn’t eat it, they lost interest.

For the first time since the war, the bears, as they were called, had everyone glued to their monitors again, but this time it was more of a window than anything else. The space program’s channel page has no sponsorship, and no breaks, just a constant stream of television from another world. Eventually, other cameras were set up, and the observers could choose between them. Every once in a while when the bears were getting too far away from the cameras they would sound a ping or play a tune, or flash a light at them to keep them nearby and interested while they set up a roving camera to follow them with, which just took a day or two more to complete.

It didn’t take long to understand that it was a family group, that there was a father and a mother, and about six cubs from various years. Without a lot more detail, they did not know how old they might be, but then again, that would be relevant to where they were from, wouldn’t it? A team of scientists figured out that the planet rotated about once every twenty-five earth hours and that their year comprised about four hundred and fifteen of those twenty-five hour days, and then somebody realized that the planet was hurtling much faster through space than the Earth was. In the end, most people just watched them. They didn’t know what was waiting for them on Titan, just a quick hop over to Saturn, but that was still being discovered. We were regularly hopping back and forth to the moon, and occasionally to Mars and Venus with a regularity that made it commonplace, but nothing more exciting than that. But regular trips to the outer planets were still a fairly new concept. It was done, just barely enough for any real research to be done. They could get there, but by the time the astronauts were home it had been ten years or more, and faster methods of propulsion were on the rise. It wouldn’t take much longer to find them.

The family of bears was everywhere you looked. You could see it for miles and miles. It was in every window, in every coffee shop, and at every transit station across town. People ate their breakfast with the bear family in the background behind them. They took showers in stalls that were made of water-proof screens and brushed their teeth with arctic bear toothbrushes.

They even set up large screens at the beach and pointed projectors up at them to see if they could make it look like the same place the bears might inhabit.

All kinds of data came back from the probe, weather-related data, rainfall, heat, and cold. Pretty soon, they had a sidebar on the channel that listed the weather projections on the planet, and before long, they saw the birds.

The birds the bears ate were enormous, with thirteen-foot wingspans and double beaks. All the birds seem to have developed into this double-headed format. They would eat with one head, and watch for the bears, and screech if they saw one with the other. Despite having two heads, they didn’t seem to share consciousness. They screeched and fluttered and before long a family of them had set up a nest atop the primary structure of the probe, and just out of reach of the bears.

This was new to them. Most of the images of the planet were devoid of trees, but what land there was had a considerable number of short bushes and grasses on them. It seemed to be a new thing to get away from the bears without having to be actively flying away.

Before long, the birds got aggressive, and started to dive-bomb the bears, and nip at their ears, but the spacemen in charge of the probe decided quickly they’d had enough of that and set off a small shock when the birds landed on the main rocket until they left it alone for good. Soon, the behavior seemed to return to normal, whatever that was.

The only thing to interrupt the daily drama of the bears was when a nearly forgotten probe near Saturn’s moon, Titan, crashed into the surface after a malfunction.

Everyone thought the probe was dead, but it continued to film video and take pictures, and record sound until it couldn’t take the pressure anymore from the nearly frozen ocean it was sinking into. The media didn’t make it back to Earth through space until an hour after the crash had occurred, but before long, there was an entire channel set up to display that new data.

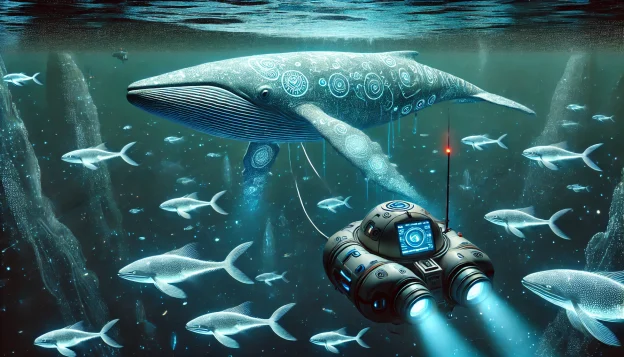

There were three hundred and fifty pictures, three minutes of video, and one clear audio recording of the song of the whales beneath the ice on Titan. They looped through it endlessly, usually with the video playing picture-in-picture style with the stills, most of them fairly fuzzy, and the audio clip of Titan whale song looping in and out of some calm and peaceful background music. There was not only life on other planets but elsewhere in our solar system.

I wanted to see the whales for myself.

I wanted to see them, and I wanted to experience them first-hand.

And since I was among the first to get the shot, I was one of the oldest people alive on the earth, and that came with some perks every once in a while. I talked my way on board the next ship to Saturn. A ship of scientists, and a couple of robots to help them clean up after meals, and me. It turns out they were taking anyone else who would sign-up and I was the only one who asked.

You know, getting to see those whales was probably the best experience of my life, but, and this is strange… It’s not all that unpleasant to go into suspended animation either. Some say it’s dreamless, but that’s not true. I had periods of deep sleep that were frequently permeated with vibrant and delicious dreams. When they brought me out I was disappointed, at least for the first thirty seconds, until I saw the whales lumbering beneath me, singing a great slow hello to us from the water.

We were positioned on this ice shelf in the middle of nowhere, there with all the equipment that we could carry with us, and all the food and all the things we thought we would need. The spacecraft sat, with the tips of its fins buried in the ice. It would never return to Earth. There was another craft in orbit around us for that. We’d lift off and leave the rest of the lander behind when we left, but there was a huge chunk of ice that we’d uncovered and cut out of the ice, moving it to the side. It was about thirty feet thick and seemed to cover just about everything. The lander kept us well anchored, and we had a great underwater sphere, big enough for five or six people to live in for a year, and we did. As soon as we were all revived, had slapped our arms and legs, and had some time to shake the reality of where we were into our heads, we sent a message back to Earth and lowered ourselves into Titan’s ocean. There was some worry that the pod wouldn’t be able to deal with the cold, and would still crack halfway down no matter what the guys who built her had said, but we didn’t know that.

It never cracked, at least not as far as I could tell, and no one ever said anything until we got back, but we were just there to take as many pictures as we could, and then get safely home. If we got any video or any sound recordings, then that was a bonus, and we went to work.

We dived into that ice-cold ocean.

While we were still up in the areas that got some kind of light, we could already see the whales. At least they were whale-like and that was enough for me. Their song was beautiful and slow and sad all at the same time. At first, we thought they were really on their own here, but before we dived another ten feet, we saw everything else that was there for us to see.

The next round comprised almost a thick layer of silverfish that were gathering together and balling into large groups as predators slid through them with gaping maws. There were so many of them they almost looked like a solid mass, but they were no bigger than a hand span across each.

We passed down through that layer and after the pressure changed a bit; we saw fewer of the small fish, hear less of the whale song, and we saw luminescent fish, jellies, and other anglers who all seemed to glow in the dark of their own accord. These surrounded us and they started to sucker onto the outside of the pod as it lowered down into the ocean. If there was any light to be seen from the surface, you couldn’t see it anymore, but the light from the fish’s bodies, mixed with the minimal lighting on the control panels, was enough to read by pleasantly.

We dropped and lowered and eventually hit the end of our tether.

It looked like the middle of space and we couldn’t see anything.

We were just about to call it quits and raise the pod to a shallower depth, where we still had something to see, but we all agreed to stop and wait a while before going up again. We spent an entire day, at least for us, twenty-four earth hours down there, each looking out of another porthole and staring out into nothingness. Then one of us, looking slightly down below, saw something in the water.

My first instinct was to reach up and turn on the floodlights, but a colleague of mine slapped my hand away. “Not yet,” he said.

I looked down, concentrated, and stared into the darkness for another hour, and then I saw it as well. It looked like a giant Koi, or goldfish swimming deep beneath us, its body lit up dimly through its light. It was massive, much larger than any of the whales up above us, but it was hard to see how far off it was. It could have been five feet across and just a few feet below us, but it seemed to lumber along in such a lazy, comfortable way that it seemed like it must be a much larger creature than that. It swam along, and almost seemed to feel its way around with large whiskers, like a gigantic catfish in the sea, and as the lights on its skin glowed just a little brighter each moment, we could see around it great oceans of those silverfish from above all around it, though this made the fish as large as a mountain beneath us.

Then it saw us.

It did almost this double take, glancing over it, and came up to investigate us. It rose to our level, and one of its eyes was larger than our entire craft. The cable above us reached into the heavens, and it slowly circled us. It then circled us in a spiral, each time getting just a little further and further away from us until it was faint in the distance. After several days, it took an entire day to get around us.

We took as many pictures and readings as possible.

Soon it was out of sight, and checking our fuel and provisions, we hit the button that would take us back up again.

We passed through the jellies, and we passed through the silverfish, being preyed upon by shark-like daggers in the water, and then back into the realm of the whales, who almost seemed to greet us with a new song. We stayed for a while, as long as we could, and then we hauled the pod back out of the water, and into the lander.

We blasted off three days later and connected with the orbiter, and soon we were all safely stowed away in our beds to sleep on our way home.

Three years journey back, and we flitted through the night sky like a shooting star and landed in the ocean near former Greenland, and were rescued by a bewildered Captain and the crew of his fishing boat.